Connecting the unconnected: the Internet of Everything is coming

Opinions expressed whether in general or in both on the performance of individual investments and in a wider economic context represent the views of the contributor at the time of preparation.

Executive summary: There are currently more devices connected to the Internet than people on the planet. Yet 1.5 trillion furtherthings may well be connected in the coming years resulting in a market potentially worth $10 trillion by the end of the decade. The advantages are clear: as with many other future trends, the Internet of Everything will allow corporates and consumers to do more with less. While still early days, leading beneficiaries include technological enablers (Rockwell Automation, Sensata, Spectris) and infrastructure providers (ARM Holdings) as well as businesses that have already begun to embrace the Internet of Everything.

Imagine aeroplanes that are able to self-diagnose which parts need repairing while still in the air, sensors in car parks that can inform drivers kilometres away whether there are vacant spaces, or thermostats in your home that can regulate the temperature regardless of you being present. Ideas such as these are no longer the realm of science fiction, but an increasing reality. With more than 2.7 billion users globally, the Internet has now become so familiar in both our work and social activities that it is almost taken for granted. However, over the coming years, the Internet’s potential will be further transformed via its increasing connection with not just the electronic, but also the physical world.

The Internet of Everything (or the Internet of Things, the terms are increasingly used interchangeably) refers simply to a scenario in which objects, people or animals are provided with unique identifiers and the ability to transfer data automatically over a network without requiring human-to-human or human-to-computer interaction. In other words, almost anything to which a sensor can be attached – be it a horse in a field, a container on a freight train, a smoke sensor in your home or a lamppost in a street – can become a node in the Internet of Everything.

Although the term was first coined in the late 1990s, it is only in recent years that the Internet of Everything has transitioned from theory to practice. Increasing processing power, storage, bandwidth and ever-lower costs (Moore’s Law) have been the main factors responsible for this change. In order for the Internet of Things to be a practical reality, five elements need to be present: at the most basic, clearly the ‘things’ themselves; next, sensors and micro-controllers. These are the components that gather and/ or disseminate data – be it location, temperature, motion, humidity, blood sugar, air quality and so on. It is currently possible to produce a simple computer the size of a grain of salt (i.e. 1mm x 1mm x 1mm) that is equipped with a solar cell, thin-film battery, memory capabilities, pressure sensors and a wireless radio antenna. The third factor is communication, either local (in the form of Wi-Fi, Bluetooth a mesh network or similar) or wider area (using 3G, LTE or even satellite). Servers are then required to collect the data, typically in either a home or an office. And finally, in order for it to be relevant, the data needs to be stored and analysed, most likely in the Cloud.

Cisco estimates that there are currently 10 billion devices connected to the Internet, a fifty-fold increase on the level reached at the start of the Century. However, according to their calculations, 99.4% of physical objects that may, one day, be part of the Internet are still unconnected. Put another way, 1.5 trillion things have the potential to be connected, equivalent to 200 connectable things per person globally. Nearer-term projections from a range of sources suggest that between 26bn and 50bn devices could be connected by 2020, resulting in a very significant market. As a consequence, consultants IDC estimate that the Internet of Everything could be worth $8.9 trillion by 2020, while Cisco calculates that the market potential for participating vendors may be $4 trillion and up to $14 trillion once the additional profit available to corporates from connecting the unconnected is incorporated. GE reaches a similar conclusion, suggesting that the Internet of Everything may create an additional $10-15 trillion of global wealth by 2022.

Even if these are very large numbers (whose accuracy it may be hard to judge at present), the logic is very persuasive. Embedded chips have the ability to enable individuals and industries to become more effective and efficient. Similar to other innovations discussed in previous editions of Helicon Thoughts, both individuals and corporates will be able to do more with less. As the Internet of Everything becomes more ubiquitous, there will be clear benefits in terms of asset utilisation, productivity, supply chain and logistics management and customer experience. The consultancy Markets & Markets calculates that the areas which will likely see the largest deployment of the Internet of Things would be (in order), industrial automation, energy efficiency, buildings maintenance. smart security and healthcare.

Many examples abound that highlight the benefits from connecting the unconnected. Taking industry first, GE is in the process of equipping the $60bn of industrial machines it sells annually with electronic sensors, enabling them to communicate more efficiently. The rationale is more accurate and faster product response times, preventive conditions-based maintenance, lower unplanned downtime and reduced costs. GE cites the scenario that around 10% of all flight cancellations and delays are due to unscheduled maintenance (costing the airline industry around $8bn annually). With their technology, aircraft have the ability to communicate with technicians on the ground so that by the time the plane lands, the ground crew is already in a position to know what needs servicing. Elsewhere, Rio Tinto has said that it is already generating over $300m in cost savings from its autonomous mining concept. Around 20% of its fleet in Australia are connected to the internet and remotely monitored from a control centre 1500km away from the mines. These machines react to the motion of other pieces of equipment in the mine and adjust to the constantly changing layout of the mine as ore and waste are removed. That major companies such as GE and Rio (among others) are embracing new concepts provides a strong endorsement for the Internet of Things.

Energy efficiency is likely to be another significant area where the Internet of Everything could benefit both corporates and consumers. French utility Suez, for example, has made smart water one of its core priorities and has already installed close to 2 million meters, yielding a revenue benefit of €350m in the last year. Meanwhile, Portuguese wind operator EDP Renovaveis has fitted its wind farms with remote monitoring and diagnostics that allow turbines to communicate with each other and hence adjust their blades in a coordinated way based on how the wind is blowing. Within the home, Nest (now owned by Google) and Hive (available from British Gas in the UK) have the ability to alter automatically the ambient conditions within households while allowing consumers also to monitor these remotely.

These are just some of the possibilities. Others include smart parking meters in cities (already present in San Francisco via Streetline and currently being trialled in Manhattan and London), cars with infotainment, diagnostics and safety equipment (according to ARM, the average new vehicle produced currently contains 60 micro-processors and over 10m lines of software code), intelligent home security systems based on keyless entry and facial recognition and wearables such as fitness bands, smart watches and smart glasses (all also already available for sale). Against this background, the OECD suggests that the average family of four will have 50 Internet-connected devices in their home by 2022, versus fewer than 10 in 2012. The number of devices present in industry, and across cities is likely to be even larger.

What might hold growth back? Consumers may be right to worry about further incursions of privacy in their lives that would arise from an Internet of Everything, while at a practical level, a lack of compatibility between different applications may limit take-up. An appropriate example might be whether a smart calorie counter (such as a Fit-Bit wearable) would be able to communicate its findings and reconcile them with an application able to detect the nutritional value of your food and/or a pair of intelligent scales. Even if all this data potentially sitting on different servers were compatible, whether individuals would want (or be obliged) to share these with their doctor or insurance company might be a different matter. For the much larger corporate market, cost and regulation are also valid considerations. Fitting (or retro-fitting) a building where each light bulb had its own smart sensor might, for example, be prohibitive. Meanwhile, the growth in smart grids may require enhanced regulation and cross-border standardisation. The increased presence of the Internet within the healthcare industry may also open up an additional range of regulatory and ethical issues.

Investors should therefore be cognisant of these potential limitations and also the current hype attached to the Internet of Everything. It is still very early days and therefore hard to gauge accurately the value chain and also eventual winners. Furthermore, many of the innovators and disruptors are currently private businesses. Beyond considering the more ‘obvious’ players such as Google and Apple, a threefold approach for gaining exposure to the theme hence seems logical, focusing on the providers of enabling applications, the businesses that have already incorporated these applications into their operations and the technological architecture that enables the Internet of Things to function.

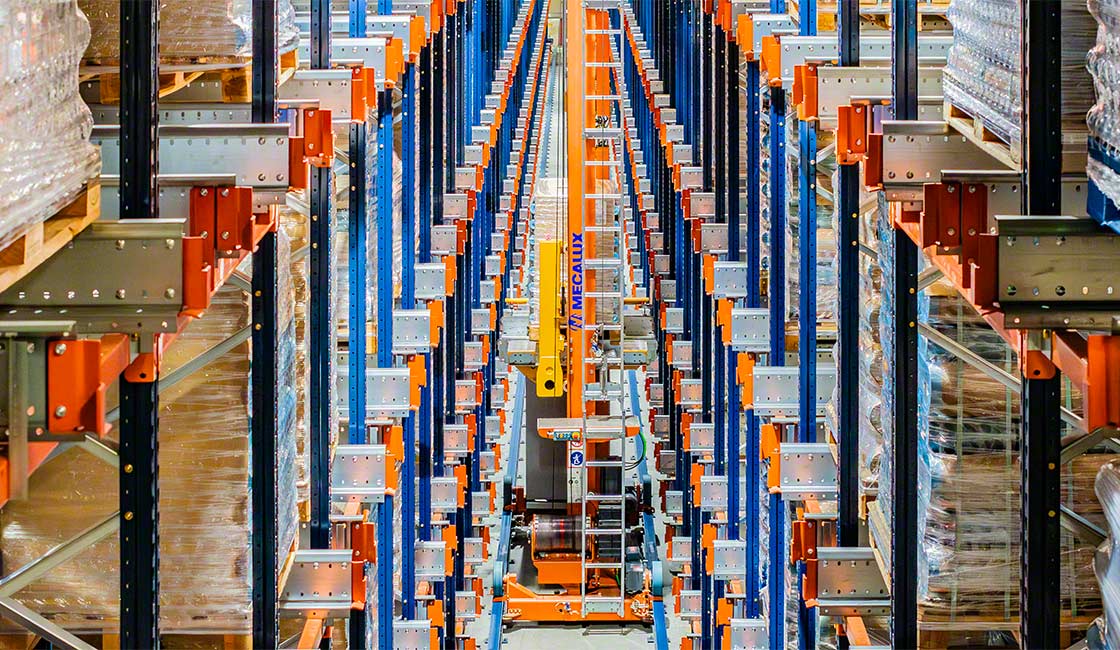

Leaders within the industrial automation space, responsible for designing and manufacturing electronic and electrical equipment, software, systems and services for commercial and consumer markets include Rockwell Automation and Sensata in the US and Spectris in the UK. Rockwell sees its addressable market as being worth up to $90bn and is targeting annualised revenue growth of 6-8%, consistent with the 7-10% forecast by Sensata. Rockwell has developed strong positions within the oil and gas, metals and mining sectors, while Sensata is more focused on the automotive and aerospace sectors. Several early movers that have already begun to embrace the Internet of Things have been mentioned previously, but in addition to GE and Rio Tinto, McKesson within the healthcare space and Jungheinrich within its forklift, warehouse design and logistics operations are other stand-out examples. Finally, within the tech space, although the markets for sensors, micro-controllers and communications equipment are relatively commoditised areas, ARM Holdings looks well-positioned, being the world’s leading semi-conductor intellectual property company with c30% market share. Over 2bn ARM-licensed chips alone were shipped last year. All these companies have consistent records of value creation for their shareholders.

Alexander Gunz, Fund Manager

Disclaimers

The document is provided for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or any recommendation to buy, or sell or otherwise transact in any investments. The document is not intended to be construed as investment research. The contents of this document are based upon sources of information which Heptagon Capital LLP believes to be reliable. However, except to the extent required by applicable law or regulations, no guarantee, warranty or representation (express or implied) is given as to the accuracy or completeness of this document or its contents and, Heptagon Capital LLP, its affiliate companies and its members, officers, employees, agents and advisors do not accept any liability or responsibility in respect of the information or any views expressed herein. Opinions expressed whether in general or in both on the performance of individual investments and in a wider economic context represent the views of the contributor at the time of preparation. Where this document provides forward-looking statements which are based on relevant reports, current opinions, expectations and projections, actual results could differ materially from those anticipated in such statements. All opinions and estimates included in the document are subject to change without notice and Heptagon Capital LLP is under no obligation to update or revise information contained in the document. Furthermore, Heptagon Capital LLP disclaims any liability for any loss, damage, costs or expenses (including direct, indirect, special and consequential) howsoever arising which any person may suffer or incur as a result of viewing or utilising any information included in this document.

The document is protected by copyright. The use of any trademarks and logos displayed in the document without Heptagon Capital LLP’s prior written consent is strictly prohibited. Information in the document must not be published or redistributed without Heptagon Capital LLP’s prior written consent.

Heptagon Capital LLP, 63 Brook Street, Mayfair, London W1K 4HS

tel +44 20 7070 1800

email [email protected]

Partnership No: OC307355 Registered in England and Wales Authorised & Regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority

Heptagon Capital Limited is licenced to conduct investment services by the Malta Financial Services Authority.