Reframing the Active vs. Passive Debate

We live in an increasingly polarised world. Politics, media and even science seem to have become hot beds of controversy where rational, open discussions seem increasingly difficult. Finance has not been immune to these trends and no subject perhaps divides investors more than the debate between the proponents of active versus passive investments. In finance, as in most other walks of life, we believe that nuance is required when making thoughtful asset allocation decisions.

In summary, we can find convincing reasons for both active and passive strategies to cohabit happily in investors’ portfolios. A considered, exploitation of their respective relative merits can help build resilient and more efficient portfolios that are optimised for the long run.

In this note we will look at the undeniable success story of Exchange Traded Funds and their meteoric rise within financial markets, as well as the risk posed by such a dramatic expansion. Furthermore, we will assess some of the drawbacks associated with the exponential growth of passive investing as well as the corresponding increase in power for the major players in the sector. We will also explore the concept of ‘active management’ and how the definition of what constitutes an active manager can vary widely. This perspective helps to explain some of the arguments surrounding the data on the long-term underperformance of some active managers. Finally, we will discuss what we believe an optimum allocation approach might resemble, by considering what both active and passive assets can bring to a portfolio.

The power of ideas

Once in a while, an acquisition comes along that gives pause for thought. We view BlackRock’s acquisition of iShares from Barclays Global Investors back in 2009 as one of the most perspicacious acquisitions of the past 20 years (on par with Google’s acquisition of little-known Android’s platform for $50m in 2005; but that is for another time). iShares had about $300bn in assets when the deal was completed, but now as part of Blackrock, this figure has grown to in excess of $2tn today. Larry Fink’s flair for buying such a business at close to the bottom of the market (in the year following the GFC) as well as his ability to understand and capitalise on one of the financial sector’s megatrends – the rise of passive investing – has to be viewed as a stroke of genius.

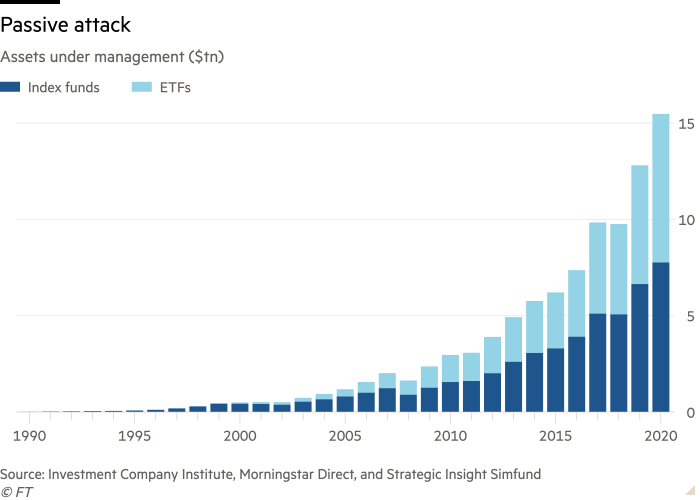

Over the past ten years, the passive fund universe has grown from strength to strength to reach $15tn of total net assets (up from less than $4tn back in 2010, per Morningstar). The total number of exchange traded funds has also grown exponentially to reach 7,600 in 2020 (per Statista). It is hard to imagine that Jack Bogle had any idea of how far his innovation would go when he created the very first index fund back in 1976. Influenced by the work of Paul Samuelson – the Nobel Prize-winning economist who wrote an influential paper in 1974 arguing that most fund managers did not beat the market – Bogle set out to create a financial product harvesting the logical conclusion of Samuelson’s research: investors are better off investing in the entire market all together.

Source: Financial Times, Investment Company Institute, Morningstar Direct, Strategic Insight Simfund

Fast forward to today, it is difficult to argue against the idea that the creation of index funds has been one of the most timely and significant financial innovations of the past 50 years. It has, helped to democratise investing, reduce costs and increase transparency for many investors, whether big or small. However, as is often the case with other similarly revolutionary innovations, the exponential growth of such a simple idea will eventually create its own set of challenges.

When size becomes an issue

The enormous growth and success in the passive assets controlled by a few major players have clearly shifted the power dynamic in markets and created a concentration issue. Consider that a Harvard study from 2017 estimated that the average combined stake of the ‘Big Three’ (Vanguard, Blackrock, and State Street) in the S&P500 companies quadrupled over the past 25 years to 20.5%. If you exclude shareholders who aren’t voting on their holdings, the Big Three accounted for about a quarter of all proxy votes for the S&P500. These are undeniably large numbers, which have almost certainly increased over the past few years. They are expected to continue rising over the medium-term. One of the key concerns related to the concentration of power of the Big Three relates to the lack of stewardship and shareholder intervention overall from passive players. They have few incentives to be active in their approaches to corporate governance.

Today, these issues are becoming even more problematic in the context of ESG and the trend towards a more general decarbonisation of our economies. We believe that a clear and positive change is underway in the overall corporate governance landscape of active managers, as a result of climate change commitments and regulation over the past few years. It is, however, very clear that – by default – a passive approach is unlikely to take these sustainability considerations seriously unless they are dedicated ESG Exchange Traded Funds.

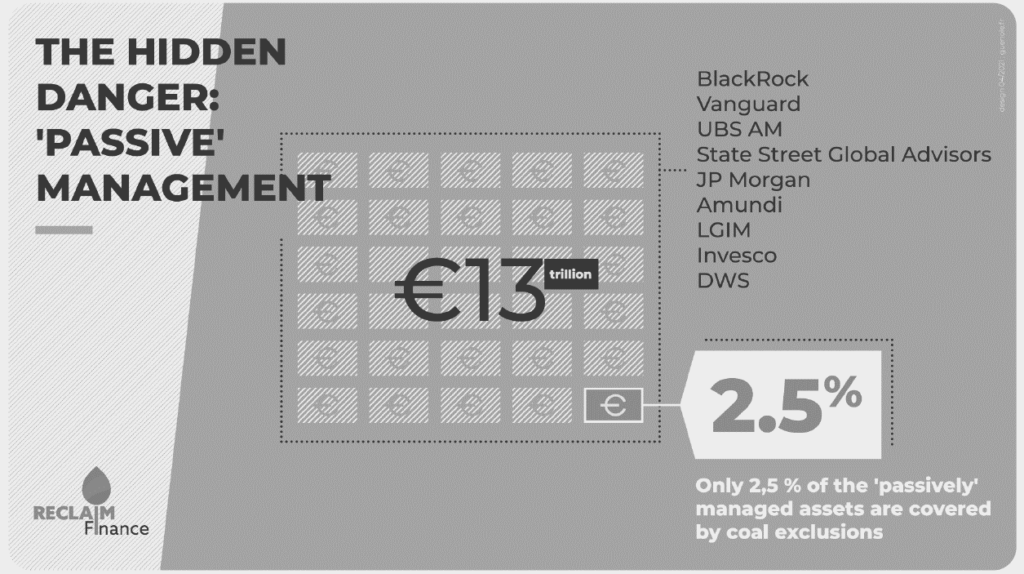

A recent study by two non-profit environmental thinktanks (Reclaim Finance and Urgewald) have looked into coal exclusion policies within the passive universe of funds (including the Big Three) and found that only 3% of total assets controlled by passive managers had such exclusions in place. The bottom line is that the increasing levels of engagement that will likely occur (and/or be required) between asset managers and corporate management teams poses a structural challenge to many passive players going forward.

Source: Reclaim Finance, May 2021

Some of the large investment consultant firms, which have been true supporters of the passive approach for many years, are now reconsidering their advice in light of this new environment. Interestingly, this change in stance appears not to be purely a function of the lack of ESG credentials held by passive managers but also a consequence of the increased risk that stems from concentration levels around a small number of mega-cap growth and tech-oriented names

Too much of a good thing?

Taking a quick glance at the sector allocation of the S&P500, the combined weight of Information Technology, Communication Services and Amazon is now well in excess of 40% of the index*. Over the past 5 years, BMO estimated that 40% of the S&P500 total returns came from just 5 stocks, the FAAMG (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, and Google (Alphabet)). Looking at a narrower index such as the Nasdaq 100 Companies, concentration here is even more pronounced. The top-ten positions represent in excess of 50% of the index. Beyond the debate about the usefulness of market capitalisation-based indices, it is clear to us that many indices today have become highly concentrated. As a result, a significant proportion of large ETFs lack adequate diversification. *As of 31 March 2021

It is therefore not unreasonable to argue that because most of the indexing universe relies on market capitalisation-based indices, it tends to lead to long periods of concentration in some areas of markets (countries, sectors, single companies) until it breaks. Think of it as akin to the ‘sting in the tail’ that has now become embedded in the system. An unsustainable feedback loop between increasingly passive allocations, momentum chasing and market capitalisation bias may well result in greater market instability, and possible eventual correction or drawdown.

In light of the above considerations, although passive investments have proved very successful on many levels and should clearly be one of the tools employed in portfolio construction, they do have some flaws which will fluctuate in importance depending on the varying market environments in which investors find themselves. The good news is that some of these concerns can be mitigated by combining both passive and active investments.

A more nuanced approach

When listening to the (often evangelical) arguments of passive and active proponents, we have always felt that the truth must lie somewhere in the middle. Although it may well be true that a good chunk of investors’ allocations to US mega-cap stocks could, for example, be easily outsourced to passive managers since this part of the market can be considered very efficient, it is equally valid that this picture would clearly change if one looks at a less efficient part of the market. A good case study would be to consider small and micro-cap stocks.

Allocating to both passive and active investments, based on the underlying level of efficiency within each chosen strategy, can provide the foundations of a solid framework to create more robust portfolios. Additionally, it can be argued that the level of passive and active investments in a diversified portfolio should fluctuate over time to reflect our understanding of the economic cycle. Another way to think about this is that there are times when investors should seek more beta exposure – perhaps in the early part of the cycle – and others when an active approach might be more appropriate as a way to better manage risks late into a cycle.

Giving active managers a chance

Firstly, it is worth considering that it may not be reasonable to expect a significant percentage of active managers to outperform their benchmark over time. In the same way that you cannot expect a large cohort of the population exceling in professional sports, true active management is hard to do and therefore should be scarce.

Another element worth considering is that much of the literature supporting the use of passive investments often relies on a rather broad definition of “what it is to be an active manager”. In other words, the persistence of outperformance (or the lack of it) can vary greatly based on one’s definition of active. As an example, a sample of US retail mutual funds ranked by their level of active share over 25 years revealed that around 70% of funds had an active share of less than 80% (see “Active Share and the Three Pillars of Active Management: Skill, Conviction and Opportunity” paper by Martijn Cremers, 2016). Active Share is a measure of the percentage of stock holdings in a manager’s portfolio that differs from the benchmark index. This study looked at active funds’ performance when the threshold for being ‘active ‘comprises factors such as a minimum level of active share and a minimum holding period. The results are remarkably different than when looking at a bigger data set. The study concluded that a combination of both high active share and longer holding period (conviction) does lead to sustained outperformance overtime. Here, the case for the ‘blanket use’ of passive strategies becomes more questionable.

Furthermore, having worked at Heptagon for over a decade and witnessing the performance and success of many of our high conviction, high active share managers, it has also been our experience that active managers that are doing quite different things from the benchmark tend to outperform more conventional managers over the longer run.

Combining passive with active in an allocation framework

Looking at our framework when considering investments for our multi-asset portfolios, we believe that the following six practical questions provide a good starting point for deciding the extent to which it makes sense to go down either the passive or the active route:

- Is the segment of the market I want to get exposure to very efficient / inefficient?

- Where do we think we find ourselves in the overall economic cycle?

- Is the current level of concentration in the underlying indices (sector, holdings etc) high or low?

- Is the active manager being considered doing things that are truly different from its benchmark?

- Is this investment tactical or strategic?

- Are ESG considerations a critical factor in getting exposure to this segment of market?

We are of course mindful that there are many other things to consider that may also be very specific to each investor given the increasingly complex nature of such allocation decisions. Of course, each of these questions can and should be refined and broken down into more detailed criteria, but we have found them a very useful initial tool to integrate into our investment process prior to a greater level of more hands-on due diligence work.

Conclusion

Since we have always considered markets as complex systems where a large number of participants with different objectives interact together, proclaiming that a passive approach is superior to an active one (and vice versa) is too simplistic and lacks the nuance needed in today’s investment landscape. Both approaches, if done properly and diligently, can deliver the desired outcomes for many investors (which can be widely varied) and we believe that combining them in a coherent and pragmatic framework has plenty of merits.

The emergence of sustainability and ESG market regulation is adding pressure to reconsider outdated asset allocation frameworks and processes. Beyond performance considerations, it is our view that investment decisions must take into account a multitude of criteria (risk, ESG, conflicts/alignment of interests, to name a few), of which many will be specific to each investor. Why choose one approach when you can have the best of both worlds?

Arnaud Gandon, CIO and Fund Manager

Disclaimers

The document is provided for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or any recommendation to buy, or sell or otherwise transact in any investments. The document is not intended to be construed as investment research. The contents of this document are based upon sources of information which Heptagon Capital LLP believes to be reliable. However, except to the extent required by applicable law or regulations, no guarantee, warranty or representation (express or implied) is given as to the accuracy or completeness of this document or its contents and, Heptagon Capital LLP, its affiliate companies and its members, officers, employees, agents and advisors do not accept any liability or responsibility in respect of the information or any views expressed herein. Opinions expressed whether in general or in both on the performance of individual investments and in a wider economic context represent the views of the contributor at the time of preparation. Where this document provides forward-looking statements which are based on relevant reports, current opinions, expectations and projections, actual results could differ materially from those anticipated in such statements. All opinions and estimates included in the document are subject to change without notice and Heptagon Capital LLP is under no obligation to update or revise information contained in the document. Furthermore, Heptagon Capital LLP disclaims any liability for any loss, damage, costs or expenses (including direct, indirect, special and consequential) howsoever arising which any person may suffer or incur as a result of viewing or utilising any information included in this document.

The document is protected by copyright. The use of any trademarks and logos displayed in the document without Heptagon Capital LLP’s prior written consent is strictly prohibited. Information in the document must not be published or redistributed without Heptagon Capital LLP’s prior written consent.

Heptagon Capital LLP, 63 Brook Street, Mayfair, London W1K 4HS

tel +44 20 7070 1800

email [email protected]

Partnership No: OC307355 Registered in England and Wales Authorised & Regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority

Heptagon Capital Limited is licenced to conduct investment services by the Malta Financial Services Authority.