Your questions on AI (answered by a human)

Opinions expressed whether in general or in both on the performance of individual investments and in a wider economic context represent the views of the contributor at the time of preparation.

If you haven’t heard of Chat-GPT or you don’t know that AI is an acronym for artificial intelligence, then you’ve probably been living on a different planet for the last few months. Sure, there’s been media and investor excitement around nascent trends such as bitcoin, blockchain and metaverse in recent years, but the ever-growing buzz around AI is perhaps on a scale akin to sentiment at the time of the launch of the iPhone. Unsurprisingly, we have received multiple inbound questions from our client base on the topic.

To summarise our core views:

1: AI is not new. Recent developments are exciting, but it is important to keep them in perspective.

2: We should think of AI as a complement to what we do rather than as a substitute, for now.

3: It is important to separate hype from reality. Even though the broad impact of AI in our lives will likely grow exponentially from here, progress will not necessarily be linear. How and when investors seek to gain exposure to the theme is also open to debate.

What follows below are the five most relevant issues that seem top of mind currently, and then our perspectives. To be clear, all the answers have been written by your author, without any help from Chat-GPT or any other AI-enhanced solution.

1: What’s different about Chat-GPT?

AI is not new. The notion of forms of artificial intelligence has been addressed by myth, fiction and philosophy since antiquity. Even prior to the excitement around Chat-GPT, an IBM-designed ‘intelligent’ computer called Watson beat human champions in the notoriously complex quiz show Jeopardy in 2011. Four years later, AlphaGo, an AI programme designed by Google subsidiary DeepMind, defeated 18-time world Go champion, Lee Se-dol. Notably, the programmers at DeepMind did not teach AlphaGo to play Go; instead, the algorithm taught itself by watching (and learning from) 160,000 professional games. At Heptagon, we first wrote on the topic of AI in 2016, arguing that it is “inherently disruptive” and that “its growing deployment in both the business and the personal sphere will enable us to do things more efficiently.”

All AI works on the basic principle of training and then inference. Put another way, give a computer big sets of data, train it to recognise patterns and make distinctions, then allow it to make inferences. This process can occur in either a supervised or unsupervised (by humans) fashion. It should therefore be evident that any AI solution is a function of its inputs. It will also be highly dependent on the hardware that underpins it. Although they appear novel and revolutionary, all chatbots are trained using large language models and reinforcement learning from human feedback. ‘GPT’, for those unaware, is an acronym for Generative Pre-Trained Transformer.

It’s also important to remember that many of us are using AI-based solutions without realising that we are doing so. McKinsey has conducted an annual survey of business adoption of AI since 2017. Five years ago, 1-in-5 of the businesses it surveyed were using AI; last year, it had grown to 1-in-2. Typically, deployments occur in one of four fashions: robotic process automation, computer vision, natural language text understanding and virtual agent conversational interfaces (i.e., chatbots).

Nonetheless, it is hard to deny that Chat-GPT has been a game-changer, even if chatbots are not new. This one is different, with more compute power and parameters (numbering over 175bn) than previous iterations. Typical response time to any challenge put to Chat-GPT – whether it be solving a problem, writing a poem, drafting a contract and so on – are answered within five seconds. The appeal is almost magical. With over 100m monthly average users at the last reported count, Chat-GPT has been the fastest-ever-growing social media/ technology phenomenon. Since Chat-GPT was integrated into Microsoft’s Bing search engine, downloads of Bing have reportedly grown tenfold relative to prior levels.

With the level of fervour around GPT, perhaps a better acronym may be to think of it as a ‘general purpose technology’ – something that could boost productivity across a wide range of industries and occupations in the manner of steam engines, electricity and computing. Do not forget, AI technology will also only get better (researchers say AI’s computational abilities are currently doubling every six to ten months), and as it gets better, it will become more engrained in our lives.

2: Where can AI help?

The number of use cases where AI in general and chatbots in particular can be deployed seems to grow by the day. A logical place to begin though would be to consider how we think about accessing information. Chatbots will help engender a paradigm shift to computers being answer engines as opposed to search engines. Logically, with more answers (from better data), it is possible to envisage outcomes where many processes can be automated with higher levels of productivity. The benefits of automation can outweigh costs by a factor of three to ten times (per McKinsey), quantified in terms of better/ greater output of a higher quality, with improved reliability. Optimists might even assert that this could imply faster economic growth.

Another perspective is that AI could also become inherently democratising, if it helped to lower dramatically the costs of expensive services in fields such as legal help or healthcare etc. AI might also allow for enhanced creativity and accelerated innovation, which could benefit fields as diverse as marketing, communications and even policy.

Microsoft has already integrated GPT-4 (Open AI’s latest iteration) into Bing, its search engine. Other productivity tools could also see AI-related enhancements. Imagine the power of a tool in Teams that could, for example, take notes or provide meeting recaps. To think about the impact of AI in other industries, consider how a car company might seek to merge real images of its logo and cars with the output of a tool like Dall-E (another AI engine) to create commercials at a fraction of the cost. Alternatively, imagine how a film studio might apply generative technology to develop an endless array of sequels, spin-offs or games built around their existing universe of characters. In financial services, expect better designed products with more optimisation.

3: Should we think of AI as a complement or a substitute?

Debates about every technology have been framed in this fashion since time immemorial. Remember the Luddites 200 years ago. These were textile workers in Nottinghamshire (led by Ned Ludd), who set about smashing mechanised cotton mills and claiming that new industrial technologies would spark unemployment. They were wrong then, just as fears about AI’s transformative effect on employment may be wrong now.

No technology in human history has ever led to a net reduction of jobs. Automation increases the productivity per worker (more can be done with fewer workers), so the market demands more workers because their increased productivity leads to more options for the goods and services that they can profitably provide. When something is automated, costs typically fall and quality increases, reduces pricing and ultimately increasing demand for that product.

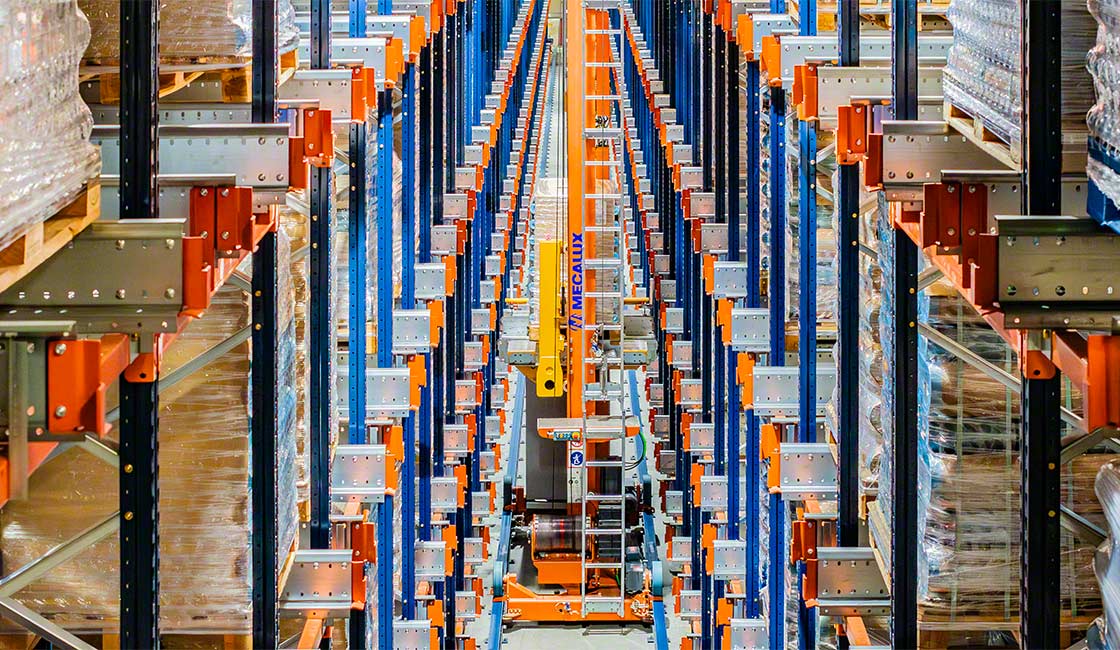

While there is a high likelihood that AI could provoke significant job destruction on a gross basis – like when cars replaced horses or lightbulbs replaced candles –the number of new jobs that could be created by the technology on a net basis will offset this. Think of evolved supply chains and new economic activity as a result of epochal technological change. We do not deny that the advent of AI may take a toll on certain businesses. Notably, however, in a recent study, Stanford professor Erik Brynjolfsson conducted an analysis of tasks required in 950 different occupations. AI could handle many of the functions, but not all: “we did not find a single one where machine learning ran the table and could do all of them.”

The arrival of AI could also help people move into better and more fulfilling jobs; users’ time could be freed up to do more important things. Within healthcare, for example, the diagnosis of many health issues could be automated, increasing accuracy for more common issues and allowing doctors to focus on more acute or unusual cases. Within finance, mortgage loan officers might spend less time inspecting and processing routine applications, allowing them to cover more customers and again deal with particularly complex issues. Indeed, the broader ability to staff, manage and lead automated organisations may become a key competitive differentiator for all businesses over time. Perhaps where policymakers should be focusing is on how best to train workers for a reshaped world.

4: What are the limitations of AI?

A different way of answering this question could be to consider how ready the world is for AI. The output we have seen from Chat-GPT and its ilk can be either wonderful or terrifying, depending on your perspective. Do not forget, AI doesn’t have a moral judgment or compass. The clue is in the name; its intelligence is artificial. Correspondingly, we should not be surprised when chatbots struggle to detect a boundary between fact and fiction or are prone to making things up to satisfy human users’ inquiries, often presenting them with a form of supreme confidence. Unlike search engines, which mostly direct people to other pages and make no claims for their veracity, chatbots present their answers as gospel truth.

For some, this debate may, of course, be moot. AI does not need to fully emulate the workings of the human brain; rather, it is about the creation of software to produce (a form of) intelligence. Even on this view, however, it is hard to escape from the charge that AI tools may reinforce misinformation and biases. Most real-world data inputs are filled with stereotypes and dominated by rich countries. Additionally, chatbots necessarily have to take content from other places to provide value. Some media sources (for example the Wall Street Journal and CNN) have claimed their licensed content has been used to train chatbots. How this issue is dealt with may have implications for the future of AI-generated content.

A massive potential regulatory minefield that incorporates both legal and ethical issues may be evolving. The key question is not just ‘can’ and ‘how’ might technology help solve any given problem, but ‘should’ it even attempt to? To build AI we need engineers, but to interpret it, to decide how it should be applied and what kind of world we want to live in requires the input of policymakers and lawyers (and even philosophers). Perhaps a significant learning from the Internet age today is to consider the unintended consequences of letting Silicon Valley programmers have an undue influence in deciding what the future may look like.

A bigger picture perspective might also incorporate the notion of technology as a form of geopolitical power. Arvind Krishna, IBM’s Chief Executive, has called it “a fundamental source of competitive advantage.” Pat Gelsinger, who occupies the same role at Intel, similarly notes that whereas “[the location of] oil has defined geopolitics in the past five decades… fabs [i.e., fabrication factories for chips] will shape the next five – this is the new geopolitics.” Against this background, expect to see an effective AI-arms race evolve. China has made clear its ambitions to be the world leader in AI by 2030. Consider that from having only been founded in 1949 and with no AI publication until 1980, the Chinese Academy of Sciences has now reached the top spot in AI research produced (per the OECD). One consequence of the above would be a world of possibly siloed information (and outputs), with different ‘truths’ revealed by multiple algorithms across the world.

5: How might investors consider gaining exposure to AI?

Most readers will be familiar with Sir John Templeton’s maxim that the four most dangerous words in investing are “this time it’s different.” With regard to AI, we may we be at the peak of inflated expectations now. Listen to Bill Gates: AI is “as important as the PC, as important as the Internet.” Sundar Pichai, Alphabet’s CEO, asserts that AI is “the most profound technology with which we are working today.” Rewind to 1999 and all a business had to do to boost its share price was add the term ‘.com’ to its name. Fast forward a few years and we saw similar with big data, then the Internet of Things, followed by blockchain, web 3.0 and metaverse. History may not repeat itself, but it can still rhyme.

AI will get better and may well change the world, but don’t expect progress to be linear.

Even the most powerful new technology takes time to change an economy. James Watt patented his steam engine in 1769, but steam power did not overtake water as a source of industrial horsepower until the 1830s in Britain and the 1860s in America. A similar argument could be made with the advent of electricity. Consider also that with the launch of the PC in 1981, the World Wide Web in 1991 (for public use) and cloud services in 2006, none of these events was a sudden ‘big bang.’ Rather, it was a long, drawn-out learning process as businesses worked out how best to use the new tools; a process of stop-start trial and error. AI will likely follow a similar pattern.

AI today is attracting great minds but also profiteers, in our view. Put another way, companies haven’t yet fully figured out how to make money with AI, but they are confident that this will come. There is also a perceived fear of missing out. Control of a new platform is too powerful a lure and companies that hesitate worry they’ll lose out.

From our perspective, AI will likely result in much greater productivity benefits and disruption relative to many other recently hyped technologies such as metaverse, hydrogen, crypto and so on. Nonetheless, for now, we believe that the clearest beneficiaries could be those providing the critical enabling infrastructure in the form of computing power and storage systems, for example. Businesses such as ASML, Equinix and NVIDIA may fall into this category. In the chatbot field, Microsoft has clearly established a lead over Google (Alphabet), but it is also abundantly clear that businesses such as Apple and Amazon will likely need to up their game. Siri and Alexa already seem tools of a different era. Others, like IBM, have been deploying demonstrable corporate AI tools for some time and may now have the chance to further improve their franchises.

Consider by way of conclusion that today, AI is still seen as somewhat of a novelty, perhaps similar to how the car was conceived at the turn of the last century. There is a famous picture which shows just one car on New York’s 5th Avenue in 1900. It is almost impossible to pick it out, given it is surrounded by horses. Just 13 years later, a similar picture was taken and not a horse was to be seen. Only time will tell whether 2023 proves to be the tipping point for AI, or just another false dawn.

The above does not constitute investment advice and is the sole opinion of the author at the time of publication. Heptagon Capital is an investor in ASML, Equinix and IBM. The author of this piece has no personal direct investment in the business. Past performance is no guide to future performance and the value of investments and income from them can fall as well as rise.

Disclaimers

The document is provided for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or any recommendation to buy, or sell or otherwise transact in any investments. The document is not intended to be construed as investment research. The contents of this document are based upon sources of information which Heptagon Capital LLP believes to be reliable. However, except to the extent required by applicable law or regulations, no guarantee, warranty or representation (express or implied) is given as to the accuracy or completeness of this document or its contents and, Heptagon Capital LLP, its affiliate companies and its members, officers, employees, agents and advisors do not accept any liability or responsibility in respect of the information or any views expressed herein. Opinions expressed whether in general or in both on the performance of individual investments and in a wider economic context represent the views of the contributor at the time of preparation. Where this document provides forward-looking statements which are based on relevant reports, current opinions, expectations and projections, actual results could differ materially from those anticipated in such statements. All opinions and estimates included in the document are subject to change without notice and Heptagon Capital LLP is under no obligation to update or revise information contained in the document. Furthermore, Heptagon Capital LLP disclaims any liability for any loss, damage, costs or expenses (including direct, indirect, special and consequential) howsoever arising which any person may suffer or incur as a result of viewing or utilising any information included in this document.

The document is protected by copyright. The use of any trademarks and logos displayed in the document without Heptagon Capital LLP’s prior written consent is strictly prohibited. Information in the document must not be published or redistributed without Heptagon Capital LLP’s prior written consent.

Heptagon Capital LLP, 63 Brook Street, Mayfair, London W1K 4HS

tel +44 20 7070 1800

email [email protected]

Partnership No: OC307355 Registered in England and Wales Authorised & Regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority

Heptagon Capital Limited is licenced to conduct investment services by the Malta Financial Services Authority.